October 15, 2022

Teach-in covers Pomona union history, rejected worker demands for living wages, what strike and picket lines would look like

More than 150 students attended a Claremont Student Worker Alliance (CSWA) “Strike 101” teach-in outside Walker Hall on Tuesday evening, a little over a week before Pomona dining hall workers will likely strike for better pay.

The teach-in, prepared and presented by student members of CSWA, explained what strikes and picket lines are, the historical and contemporary context for the upcoming Pomona strike and broader implications of organizing at Pomona for the Inland Empire and beyond.

Pomona dining hall workers, which includes workers at Frank, Frary and Oldenborg dining halls, as well as the Coop Fountain and Cafe 47, have been collectively organizing since at least 2010. They won representation by the Unite Here! Local 11 union in 2013, negotiating three-year contracts with Pomona College in 2013, 2016 and 2019.

On July 1, the workers’ previous contract with Pomona College expired. Negotiations for a new contract, for which workers are seeking a minimum wage of $28/hour, have stalled, with Pomona only offering a $1.35/hour raise within the year.

The minimum wage for Pomona workers is currently $18.60/hour, “which is by no means a livable wage in LA County,” said Arun Ramakrishna PZ ’22.5 at the teach in. Ramakrishna works for Unite Here! Local 11 as the Pomona dining hall workers’ union representative.

As a result, Pomona dining hall workers will vote on whether to authorize a strike on Oct. 20. Oldenborg kitchen staff Benny Vargas told The Student Life that the strike vote is “very likely to pass,” with an “overwhelming majority” of dining hall staff having already signed pledge cards in support.

“There’s just way too large of a gap between what Pomona College is offering and what the workers are saying that they need and deserve,” Ramakrishna said. “That’s why workers are thinking of taking such a courageous and drastic action to put pressure on the college.”

If the workers do strike, Cafe 47 and Coop Fountain will close, while Oldenborg, Frank and Frary will function at limited capacity with temporary workers, Jacquelin Tsai SC ’25 said at the teach-in.

During the strike, workers and students will form picket lines outside of Frank and Frary, encouraging students not to cross them to eat at the dining halls. In addition to the “ideological solidarity” students can show by not crossing, if Pomona students swipe into other dining halls Pomona College will have to pay those dining halls.

“Pomona will be losing a lot of money during this strike…we really want them to feel that financial burden,” said Jessica Shen-Wachter SC ’24 at the teach-in.

The strike will also have implications for labor negotiations and organizing beyond Pomona, said Melia Oliver SC ’24.

“The negotiations that are going on at Pomona right now are setting the standard for what’s happening at Pitzer with their current contract negotiations, which also is interconnected to the labor fight around the Inland Empire,” Oliver said.

Cameron Quijada SC ’25 pointed out that organizers at University of La Verne and Whittier College labor organization are working directly with organizers at Pomona.

“La Verne [and] Whittier [are] literally citing what’s happening at [the Claremont Colleges] to get better raises for them,” Quijada said. CSWA members attended a delegation of Whittier workers on Sep. 30, while both Whittier and Pomona student organizers attended a delegation of La Verne workers on Oct. 13.

Organizing at Pomona is made possible in part by the momentum from Pitzer workers unionizing earlier this year, said Adam Osman Krinsky PO ’25 at the teach-in. Earlier this year, CSWA also mobilized hundreds of students for a Labor Day rally in support of Pomona workers.

“It’s no mistake that when Pitzer organized their union, we now have the momentum here at Pomona to fight for dining hall workers’ pay raises. These things are all building up on each other,” he said.

Oliver also warned students at the teach-in that Pomona College will put out messaging depicting workers as lazy or framing itself as financially strained and innocent.

On Oct. 14, Pomona administrators sent an email to all Pomona students with the subject line “Dining Contract Negotiations Update,” claiming that the wage demanded by workers was “not a realistic demand we are able to meet.”

In the face of this rhetoric, it’s important that students “are prepared for this and can deconstruct it ourselves and also share with our peers why this actually isn’t true,” Oliver said, citing the college’s $3 billion endowment.

Quijada said the large turnout and supportive atmosphere among students makes her optimistic that the necessary conversations are happening.

“There’s a lot of campus conversation going on surrounding this Pomona strike,” Quijada said. “At the end of the day, CSWA doesn’t want to be the ones that are giving out all this information. We want students to know it and to be well versed in the history of the Pomona union and we want students to know why the Pomona union is important and then for them to have these conversations with their friends.”

CSWA members have been clipboarding, or asking students for their contact info to be mobilized if a strike does occur, at Frary, Frank, Oldenborg and Mallott dining halls since Monday. They have gotten the contact information of 722 students, including at least 454 Pomona students, in the past week. CSWA’s weekly organizing meetings regularly have over 60 attendees, according to Quijada.

“We actually collectively have a tremendous amount of power. If the managers and the administration see that these picket lines are huge, that is super scary and intimidating to them and it makes them look super bad,” Oliver said.

Appendix: A brief history of Pomona labor organizing and Pomona College suppression

Compiled using information from the Strike 101 workshop and sources from Mara Halpern’s 5C Labor Fight Archive

Though Pomona dining hall workers successfully won union representation in 2013, they had to overcome efforts by Pomona College to undermine their organizing to do so, and continue to face opposition today.

The fight for union representation publicly began when the group Workers for Justice launched a campaign for union representation, full-year employment and less expensive health insurance coverage in March 2010.

Pomona administrators granted the latter two demands in Nov. 2011, which Workers for Justice celebrated as a win but also framed as an effort to placate workers and blunt unionization efforts.

“They’re giving us all these things, [but] they can similarly take it all away from us,” Christian Torres, a chef in Frary at the time, told The Student Life.

The next week, Pomona enacted a policy prohibiting dining workers from having prolonged conversations with students or other non-staff members within dining halls, even when the workers were on break.

That same week Pomona began checking the work authorization documents of 84 of its employees, firing 17 of them when they could not provide documentation by Dec. 1, 2011.

Though administrators said the reason for the search was to prevent Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) intervention, organizers and school faculty pointed out that the employees subject to the search had been at the school for many years without issue, and that immigration-related searches have historically been used for union-busting purposes.

The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) filed a complaint against Pomona College alleging retaliation against pro-union workers on Dec. 8, 2011. The college settled with Workers for Justice in Feb. 2012, agreeing to roll back the student-worker communication policy but not admitting guilt for retaliation.

After three years of organizing by Workers for Justice for a vote and neutrality from Pomona College, Pomona dining hall workers voted 57 to 26 in favor of joining Unite Here! Local 11 in April 2013. The vote followed other successful unionization votes that year by workers at Georgetown University and the University of La Verne.

The union vote protected the workers’ ability to raise concerns with management and form delegations, but conflicts over working conditions and administration policies still remained.

In Sep. 2020, Pomona College furloughed hundreds of campus staff due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a move that faculty and other community members protested for harming the most vulnerable community members instead of placing the burden on faculty and administrators.

In negotiations from Aug. to Oct. 2022, Pomona College rejected demands by workers for a raise to a living wage of $28/hour, leading to the organizing around a potential strike unfolding now.

Commentary

Palestine

Palestine

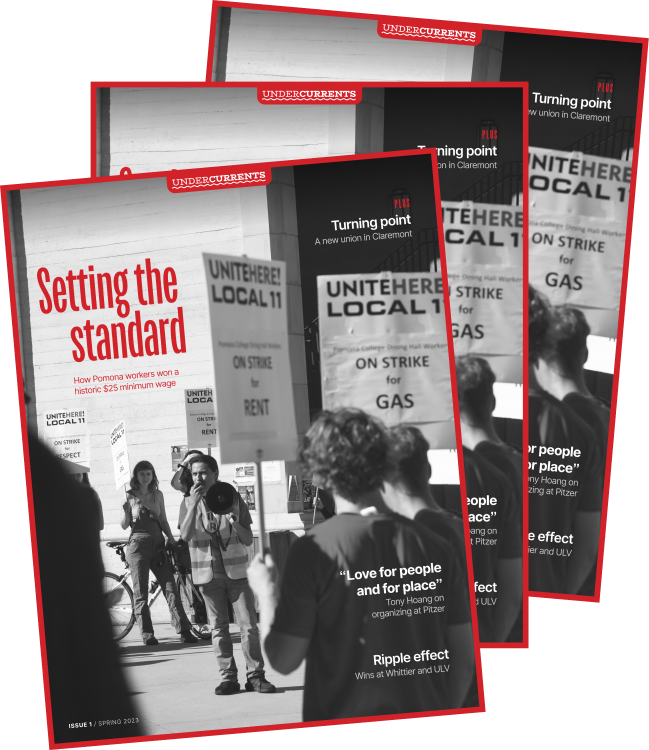

Undercurrents reports on labor, Palestine liberation, prison abolition and other community organizing at and around the Claremont Colleges.

Issue 1 / Spring 2023

Setting the Standard

How Pomona workers won a historic $25 minimum wage; a new union in Claremont; Tony Hoang on organizing

Read issue 1