October 23, 2023

Two UCR professors, one a WWRC board member, discussed the history of labor and environmental justice organizing around Inland Empire Amazon warehouses at a CSWA event.

A political education event organized by the Claremont Student Worker Alliance drew an audience of about 30 students on Saturday, October 7, to learn about the history of organizing around Amazon and other warehouses in the Inland Empire.

The event comes amidst ongoing pickets by striking Amazon delivery drivers at the nearby KSBD warehouse. Dozens of Claremont students joined their picket last Monday, and they are scheduled to strike this Friday, October 13. These actions are a response to Amazon terminating their contract with a subcontractor that employs 84 workers, after the workers delivered a petition for better working conditions and unionized under Teamsters Local 396.

Ellen Reese and Juliann Emmons Allison, both professors at the University of California, Riverside, presented at the event. Their research on environmental and labor exploitation in Amazon’s warehouse system was recently published by UC Press as the book Unsustainable: Amazon, Warehousing, and the Politics of Exploitation.

The speakers told the audience that the Inland Empire has been a logistical hub – full of trucks, trains, and warehouses – for a long time.

“If you look back through the major industries that have been in this area,” Allison said, “it has been just a history of things moving through this area and all the way to the West Coast. If you were to step back and look at train lines, you would see that we’ve got a couple of big lines that chug, chug, chug out of the west and hit the Mississippi. So we’ve been feeding and supplying the rest of the nation for a very long time.”

This historical infrastructure and coastal location also make the Inland Empire a desirable place for modern warehousing. As the largest private employer in the region, the professors said, Amazon is the most notable example of this phenomenon – and therefore “the biggest of a large number of entities that are contributing to a lot of terrible things.”

Allison noted that warehouses are an “indirect source” of harm from an environmental perspective: they generally don’t emit pollutants themselves, but they increase truck and train traffic in the surrounding area. This has local implications, including public health effects, to go along with the global problem of fossil fuel use.

And because transportation corridors such as railways and freeways tend to bring down the land values of adjacent areas, she said, “you’re going to find people who are more economically disadvantaged living in those areas. And it becomes a situation where most of these people are going to be communities of color.”

The professors’ research has found that this situation is compounded by the precarity of warehouse jobs. “People are impoverished,” Allison said. “High injury rates [are] something we see across the industry, visited upon blue collar warehouse workers.”

The rate of serious injuries at non-Amazon warehouses was about 3.2 per 100 full time employees per year in 2022, according to a report by the Strategic Organizing Center based on OSHA data. At Amazon warehouses, the rate was more than double, at 6.6 per 100.

Allison also noted that when serious injuries leave workers unable to continue their warehouse jobs, or when they are fired for other reasons, the challenges continue. “Blue collar workers just generally don’t have the access typically to the education, the tools and the training that allow them to transition when they lose their job or get laid off.”

For a long time, Reese said, labor organizing in the Inland Empire failed to keep pace with the rapid expansion of the warehouse industry.

According to Allison, struggles for environmental justice were the first to take off. She cited the Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice in Jurupa Valley, which traces its roots back to local resident Penny Newman’s 1978 struggle to clean up the mismanaged Stringfellow Acid Pits.

When it was officially founded in 1993, CCAEJ broadened its approach, Allison said. “It kind of bridged the focus of folks upset about the Stringfellow Acid Pits, like, bad companies dumping stuff in our area, to what had happened with the economy and the growth of these warehouses. So that was kind of a jumping off point for the growth of a whole lot more.”

Reese, who focuses more heavily on labor while Allison studies environmental organizing, mentioned the International Brotherhood of Teamsters as an early example of worker organizing focused on warehouses. Local 63 of the Teamsters has historically organized truck drivers and warehouse workers in Southern California, she said. And while acknowledging that warehouse growth has historically outpaced that of unions, the professors believe that worker organizing is catching up.

Reese and Allison said that organizing around warehouse labor really began to gain momentum around 2008, with the public launch of the Warehouse Workers United campaign. 2011 brought the establishment of the Warehouse Worker Resource Center in Ontario, which became a hub for workers to organize and share with one another.

2019 was the year that groups like these really began to set their sights on Amazon. Labor organizations including the Teamsters and WWRC, as well as local environmental justice organizations, began working in tandem with Amazon warehouse employees who had decided to form unions of their own. This escalated into 2020 and beyond. “It became kind of a pressure cooker,” Allison said.

Organizers’ focus on Amazon and the rapid spread of its warehouses gave rise to new labor groups, including Inland Empire Amazon Workers United, which the speakers noted is actively organizing at Amazon’s San Bernardino Air Hub facility (also called KSBD).

Amazon Workers United organized two walkouts at KSBD last year, demanding a $5 increase in base hourly pay and better heat safety. The workers are now demanding $25 base pay, heat hazard pay, and other improvements to working conditions.

At the ONT8 Amazon facility in Moreno Valley, workers are organizing to join the Amazon Labor Union, a new group which previously successfully unionized workers at the JFK8 facility in Staten Island, New York.

On a statewide level, labor advocacy resulted in the 2021 passage of Assembly Bill 701. This unique legislation gave workers in warehouses like Amazon’s the legal power to fight unreasonable work quotas, which often prevent them from using bathrooms and taking breaks.

And environmental advocacy by groups including CCAEJ as well as the national nonprofit Earthjustice has led to victories as well. In 2021, the latter group achieved a legal decision mandating that the new World Logistics Center in the Inland Empire attempt to mitigate its negative effects on the environment.

Around the same time, the South Coast Air Quality Management District adopted a rule based on the indirect harm warehouses cause the environment, requiring that they either use zero emissions vehicles or pay fines to help offset the emissions of their trucks.

Many cities, including some in the Inland Empire, have even passed moratoria preventing further warehouse construction, the speakers said.

Audience questions after the presentation largely focused on the implications of organizing against the expansion of warehousing and the exploitation of workers and the environment. Topics raised included the future of work and the possibility of economic degrowth, as well as the potential for intersectional organizing with groups like the Black Lives Matter movement.

Francisco Villaseñor PO ‘25 asked about the potential for hope in the complex and often frustrating landscape of organizing against entities like Amazon. “It feels almost like a David versus Goliath sort of scenario,” Villaseñor said, “with the tech that Amazon has and the way it’s expanding and the way they’ve taken advantage of folks for a long time.” He asked how Allison and Reese stay motivated: “You wrote a whole book about it. What is making y’all feel like that level of hope to keep this work moving forward?”

Allison responded that ongoing labor organizing is yielding results. “Organizing is continuing, and there are different groups trying to do it in different ways, you know? Because it is like David and Goliath, and the big enemy is Amazon.”

She praised labor organizers for collaborating with students and other local communities, and for persisting when conditions are so difficult. “The workers have been amazingly courageous in doing the organizing that they’re doing.”

Commentary

Palestine

Palestine

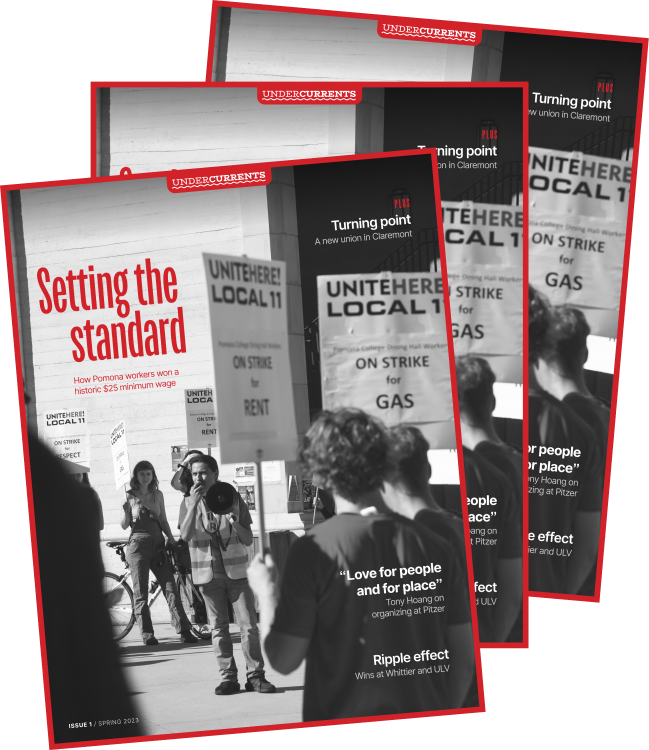

Undercurrents reports on labor, Palestine liberation, prison abolition and other community organizing at and around the Claremont Colleges.

Issue 1 / Spring 2023

Setting the Standard

How Pomona workers won a historic $25 minimum wage; a new union in Claremont; Tony Hoang on organizing

Read issue 1