May 6, 2024

A brutal arrest was only the beginning of weeks of violence at the hand of Pomona administrators.

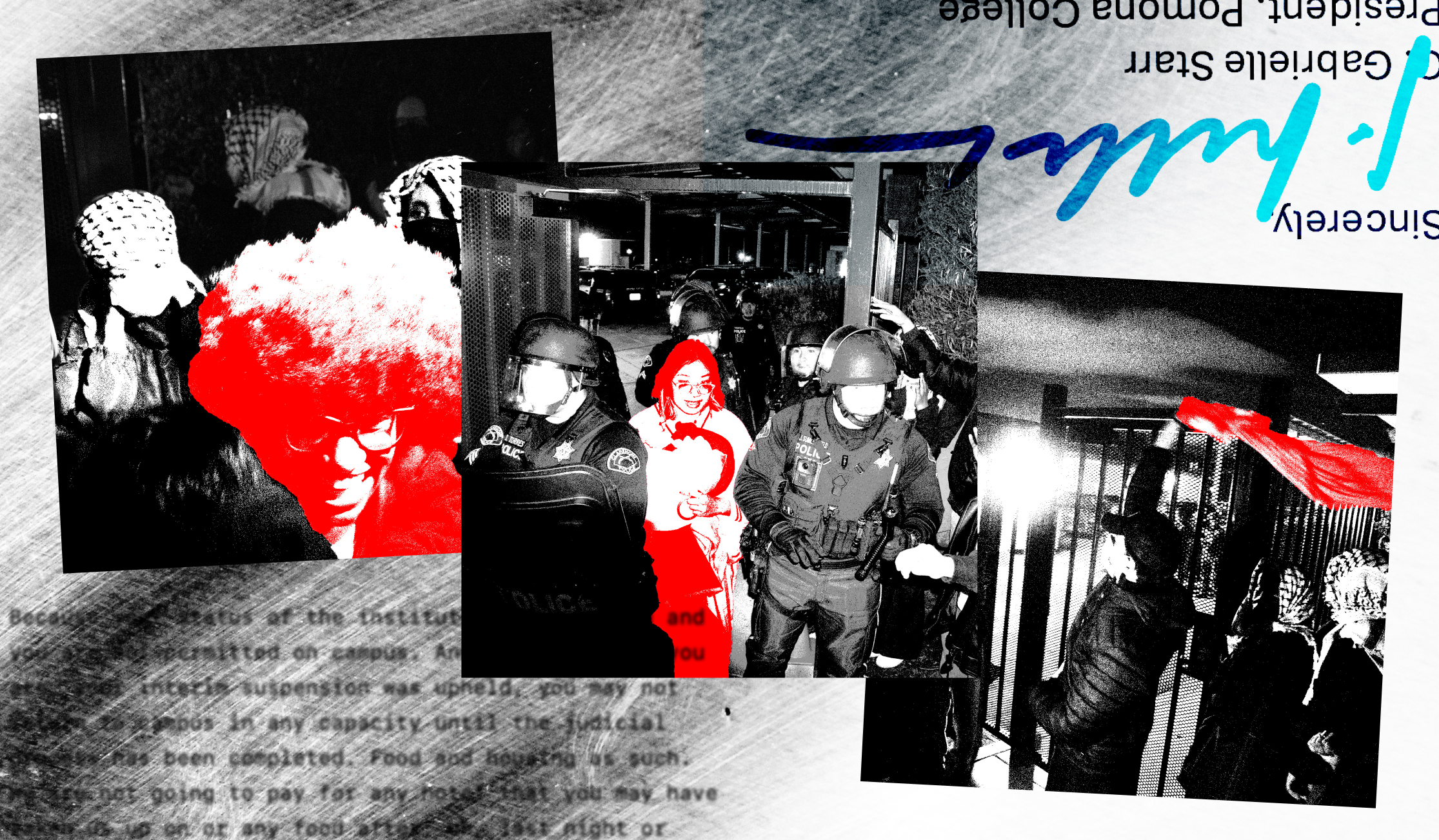

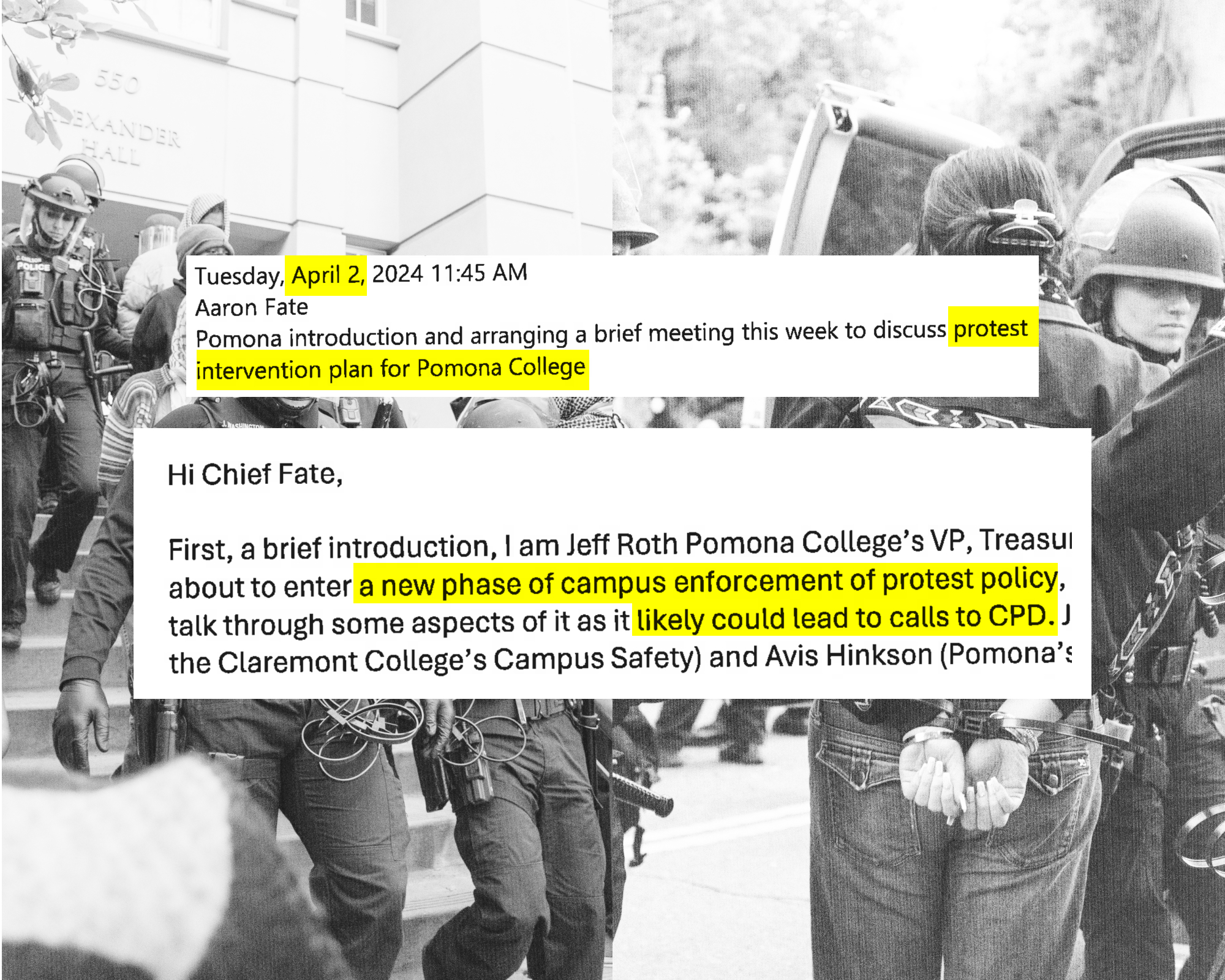

On April 5, Pomona President Gabi Starr’s decision to call in five police departments of riot police to arrest 19 students participating in a divestment sit-in rocked the campus. In the past month, administrators at UCLA, Columbia University, NYU and dozens of other schools have similarly called in harsh riot police crackdowns of student actions for divestment from Israeli genocide. The crackdowns have resulted in the arrest of more than 2,000 students and faculty across the country.

Israel has killed over 34,000 Gazans since Oct. 7, and is currently targeting Rafah, where 1.5 million Gazans have taken shelter after Israel’s indiscriminate bombardment of northern Gaza.

For the seven arrested Pomona students, the forced removal was only the beginning of several weeks of violence at the hands of Pomona administrators. Among other things, Pomona College and Campus Safety leaders had students held in jail for hours so suspension letters could be delivered to them there; immediately suspended, with no time for students to retrieve belongings; put through a food reimbursement system that made it almost impossible to actually get reimbursed; and finally, pressuring students to have the school book them flights out of the area entirely and threatening to contact students’ family members when they refused.

On April 15, Undercurrents spoke with Minh Truong ‘24, Njoka Njue ‘27, and Sinqi Chapman ‘27, three arrested Pomona students, as well as a fourth arrested student who asked to remain anonymous, to discuss their experiences in jail and afterwards.

Banned from campus, Njue, Truong and Chapman were temporarily living together at a friend’s house in Long Beach. They took the call from a park on the warm day. Alternating between joy and rage, laughter and expletives, the three arrestees recounted their experiences since their arrest.

April 5 marked eight days after students from the Pomona Divest from Apartheid campaign set up an eight-panel Apartheid Wall at the Smith Campus Center, and an encampment surrounding the wall. After ignoring the wall for almost the entire duration of it being up — students were never even told to take the encampment down prior to April 5, they said — Dean of Students Avis Hinkson suddenly called in trucks of Campus Safety officers and facilities workers at around 1 p.m. to forcibly remove the wall.

Within half an hour, administrators had overseen the removal of five of the eight panels. Videos show facilities workers using power tools to take apart the walls as students clung to them in defense. The workers also cleared what remained of the surrounding encampment, including a large supply tarp that contained dozens of students’ personal belongings.

Soon, a crowd of chanting students gathered to defend the remaining three panels. By 3 p.m., Campus Safety and facilities workers appeared to give up on removing the panels, leaving the area. At 4 p.m., 19 students entered Alexander Hall, deciding to stage an immediate sit-in in President Gabi Starr’s office to demand divestment.

Starr immediately threatened all students with suspension. When the students refused to leave, she apparently authorized a police response. Several police cars first arrived around 5 p.m. By 6 p.m., 25 police vehicles from Pomona, Claremont, La Verne, Covina, and Azusa police departments lined the streets by Alexander Hall. More than 20 officers, who appeared to be in riot gear, then entered the building, carrying shields, batons, and crowd control weapons.

The anonymous student that was interviewed emphasized that police were called on a peaceful sit-in. “We were [just] sitting on the ground. Nothing really happened in the room.”

Despite this, Chapman described the various measures of violence inflicted upon them during the arrest, “They yanked us off of our feet. And tied the handcuffs extremely tight. The first person that got arrested, they did this on purpose. They’re like a small person and they were sitting criss-cross applesauce and they yanked them off their feet.”

The arrest left several students with injuries.

“My hands are like scarring over from the zip ties [from] bleeding,” Chapman said, “and I still have the knife marks on like the palm of my hand,” referring to when police used knives to cut the zip ties at the station.

Truong also shared photos of cuts on their wrist, which remained several days after the arrest, with Undercurrents.

The anonymous student described being grabbed, kicked and having their head hit against the police van in the course of their arrest.

“I stood up peacefully. They grabbed us, two officers per arrestee. I mean, they were in full riot gear. They had chemical weapons on them,” the anonymous student said, referring to what appeared to be 40mm grenade launchers typically used to fire tear gas and pepper ball rounds.

This student was pushed against the wall as the police did a maneuver known as chicken winging. They grabbed both of the arrestee’s arms and pulled them up, which concerned the arrestee as they had hurt their shoulder earlier that day. Officers then kicked the arrestee’s legs to spread them apart for a search.

During this process, the student recalled that their keffiyeh had become undone and was completely obstructing their vision. As officers led them down the stairs and through the crowd, they could barely make out where they were going.

As they were being forcibly put in the back of the prison van they said, “I hit my head on the top of the roof on my way in. [It was] a very physical, very rough experience. I had to rely on my fellow arrestees to try to get my keffiyeh outta my face just so I could see.”

All 19 students participating in the sit-in, as well as one student in the crowd outside, were arrested and taken to the Claremont Police station by 7:30 p.m. One video captured by an Undercurrents reporter showed police rejecting requests by a lawyer to speak with the students.

Truong told Undercurrents that when arrestees asked for a lawyer or food, they were threatened and told they would be kept in jail longer, even being told that police would keep them locked up overnight.

Two students were also isolated and questioned by police officers, Njue and the anonymous arrestee said. The anonymous arrestee emphasized that the students were Black and Indigenous.

“The cops were racist the whole time. Big surprise, right? They were particularly disciplinarian against our Black comrades,” the anonymous student said.

When students were asked to give their personal information to the police, they had to do so with other arrestees present. All of the students’ medical information and their social security number, could be heard by anyone in the nearby vicinity.

One arrested student also had a medical condition called POTS, for which they needed to have salt. They asked for salt, but were given orange juice instead, the anonymous arrested student told Undercurrents — even though the police told a lawyer outside, on video, that “we have salt,” and that “if [the student] asks for it they will be provided with it.”

Claremont Police released the first arrestee at 9:24 p.m., almost three hours after the first arrests and more than two hours after the last. A line of police officers walked up to the gate where a crowd of hundreds stood, cheering and shouting Palestine liberation and anti-police chants, and let the arrestee through.

The police divided students based on perceived gender, releasing all five masculine-presenting arrestees by 9:40 p.m. Police released the first five feminine-presenting arrestees released around 9:50 p.m.

Police didn’t release another student until an hour later, however, and didn’t release the last seven students until after midnight — apparently so that Director of Campus Safety Mike Hallinan could deliver them their suspension and ban letters from Pomona in jail.

The anonymous arrestee, who police released before midnight, said that they received their suspension letter via email from the Dean of Students at 11:30 p.m. that night.

Truong was the last to be released, at 12:17 a.m. They said that they saw Hallinan walking in and out of the police station, and personally handed Truong their suspension letter before the police processed them and took their mugshot.

Chapman said that she also received her suspension letter in jail.

“I literally had to sit in a jail cell longer because Pomona College and the police department are one unit,” she said.

In an email to suspended students on April 6 reviewed by Undercurrents, Dean of Students Avis Hinkson wrote that “it is our practice that when a student is interimly suspended, the student leaves the area within 24 hours.” Associate Dean of Students Josh Eisenberg, who has previously answered Undercurrents’ questions about the student code, did not respond to an email asking for clarification on whether this means students typically have 24 hours of access to their dorms before being suspended.

When asked how much time the students had to move out of their campus housing after being released from the jail, Truong, Njue and Chapman emphatically responded, “Zero.”

“We could’ve been sleeping on the street and they did not offer us any other place to go,” Njue said. “We didn’t have food ’cause we were locked away from the dining halls.”

Chapman described her initial feelings of confusion after being released from the jail. “I was literally the last one released from jail at 12:20 AM and was like, I have no idea what’s happening right now.”

Chapman and Njue were fasting for Ramadan, which is typically broken at sundown each day at 7 p.m. That meant that the arrest and suspension made the food insecurity especially rough.

Truong said she ended up going home with one of her close friends. “They barely had any food at home and they made me some ramen and I went to sleep still hungry ’cause like, you know, I was out all day [in jail].”

It wasn’t until the day after the arrests, on April 6, that the arrestees were sent an email by the Dean of Students, Tracy Arwari, detailing the next steps of the students’ interim suspensions. “They outlined that they would offer us a food reimbursement or an undisclosed hotel […] The details were unclear.”

Because there was no way to access their dorms immediately, the anonymous arrestee and Njue had to wear the same clothes for several days, they said.

“I only had one pair of clothes. You’re not being prepared to move out. So I had to stay in those clothes for multiple days. I didn’t have my toothbrush, I didn’t have deodorant, I didn’t have anything. So we were all sitting around in the same clothes looking around for housing and being evicted for a long time,” Njue said.

It wasn’t until the day after the arrests, on April 6, that the arrestees were sent an email by the Dean of Students, Tracy Arwari, detailing the next steps of the students’ interim suspensions. “They outlined that they would offer us a food reimbursement or an undisclosed hotel […] The details were unclear.”

The only way the arrestees could get access to their belongings was if they were accompanied by campus security — and some didn’t feel safe doing so.

“For me personally, I do not feel safe and I don’t feel comfortable [and I’m] traumatized and don’t want camp sec to follow me to go back to my room to get my stuff. That’s such an invasion of privacy. It’s so unjust that I was fucking evicted and housing insecure in the first place and now y’all want [campus safety] to follow me around,” Truong said.

Truong hasn’t been able to see their emotional support animal since their arrest. They expressed longingly, “My cat bro, I haven’t seen my ESA and it’s been so long. Oh my god.” Their friend is currently taking care of the cat until Truong can return to campus.

Food reimbursements were also difficult for the students to sort out due to strict requirements for approval and miscommunication, students said.

Chapman said that although she had sent in multiple days worth of receipts, only one day’s worth of food was ever reimbursed. Njue said that, because they only had $20 in their bank account, they tried to avoid purchasing food directly to begin with, which prevented them from being reimbursed.

When they did try to get reimbursed for a grocery receipt, a Dean of Students office staff member told them that the receipt needed to have their name on it, and refused to reimburse it.

“It was a Target receipt. It’s a fucking grocery store,” Chapman cut in as Njue recounted the exchange. “Why would Target receipts have [your name] on it?”

Ultimately, Njue had to rely on friends and family.

“I had to rely on other people for food. I was sleeping on different people’s couches for days.”

On Monday, the seven arrested Pomona students were given the chance to appeal their interim suspensions by submitting an appeal letter to the Preliminary Sanctions Review Board, composed of two students and two Deans from the Dean of Students office.

All seven students did so, submitting letters pointing out the disproportionate severity of interim suspension in response to a two-hour sit-in. But the PSRB initially declined to approve or reject the appeals, instead giving all seven students an additional 24 hour extension — until Tuesday 10 p.m. — to rewrite and re-submit the appeals.

Guessing at what might have gone wrong with the initial letters, the students rewrote their letters and turned them in once again.

On April 10, the students were informed that PSRB had upheld four of the suspensions and lifted the other three. That meant that three students were able to return to campus and access dining halls, but four still couldn’t. All who remained suspended were students of color; one was first generation and low income. All seven students were still awaiting JBoard hearings for their final sanctions.

No information was provided about why each appeal did or did not go through, students said.

“They were super vague about why they approved some and didn’t approve others. They just cited Article Two of the student code handbook. Which if you go to Article Two it’s a super long section outlining all the power of the judicial board,” the anonymous student, who had their appeal rejected, said.

On April 11, the day after the decisions were announced, over 700 students walked out of classes in a rally to demand divestment in solidarity with the 20 Claremont students that Starr had arrested.

On the same day, Dean of Students Tracy Arwari called all four interviewed students, pushing them to let the college book them immediate plane tickets home. Though presented as an offer, students described feeling pressured, and even threatened, to quickly accept.

Chapman recalled how she asked Arwari, during the phone call, if there was any way this information could be sent over an email. Arwari insisted that the transportation be arranged over the phone.

When Chapman expressed that she needed extra time to think about what to do, Arwari asked her to respond with her decision the next morning. Arwari also told Chapman, Njue and Truong that the school would stop providing housing and food reimbursements, giving varying cutoff times — either one that already passed, on the night of April 10, or sometime on April 11 — to each of them.

During this time, arrested students shared their experiences with each other, and decided to each send emails to Arwari putting the phone conversation — and any subsequent responses from Arwari — in writing.

In her email to Arwari, Truong said that she was overwhelmed with figuring out immediate food and housing needs, and unable to quickly make a decision about transportation.

“As a first generation, low-income college student, it has been unclear the circumstances following my access to food, housing, and safety support from the college. It is hard to plan much of anything at this point, much less make a decision about flying home,” she wrote.

Truong also shared that they would feel unsafe returning home, mentioning a history of physical violence.

“This is quite personal for me to share, but I feel like it’s important that whoever is making these housing decisions knows that I do not feel safe at home … I usually do not return home for my safety,” Truong wrote to Arwari in the email.

Arwari first replied later that day, thanking Truong for “sharing your circumstances” and saying that the school could arrange transportation somewhere other than Truong’s home. But the next day, Arwari again urged Truong to let the school arrange transportation quickly — by 5 p.m. that day — and said that the school was going to contact Truong’s parents.

“I understand that you are taking time to think through how you want to proceed. It is also important for you to know that since your status at the College has changed and you are no longer on campus, we will be calling your family/ emergency contact today to notify them of your interim suspension.” Arwari wrote to Truong on April 12.

On April 16, Truong’s parents received the letter, informing them that Truong had “participated in disruptive activity at Pomona College on Friday, April 5. This disruptive activity resulted in your student’s arrest.”

The letter also falsely stated that “as of Saturday, April 6, we offered to pay for your student’s transportation home (or to another location of their choice) while they are interim suspended.” Truong did not receive any offer of transportation support until April 11.

The anonymous arrestee, who also received a call from Arwari, said that it felt like the Dean of Students’ office was trying to “ship us out of the area” without leaving a paper trail.

When Undercurrents interviewed the four arrested students, they were continuing to figure out housing and food off campus day-by-day, awaiting the scheduling of Judicial Council hearings that would determine their final sanctions. Most of those hearings have now concluded, though Undercurrents has not yet gotten information about the results.

In the meantime, Starr sent an email appearing to avoid responsibility for the arrests, and urging “dialogue.”

In an April 15 email about an upcoming town hall, Starr wrote that, “When we first scheduled this town hall last month, none of us thought that it would occur in the aftermath of Claremont police answering a call for help to Alexander Hall and the arrest of students.”

“In a vote last Thursday, the faculty as a whole expressed clearly that they do not want to see a heavy police presence on our campus. I could not agree more with that sentiment,” she wrote. “In these final weeks, we have a chance to work toward a better path. Let’s take it together. I hope to see you this Thursday (April 18) for our community conversation.”

When reflecting on this whole process, one of the arrestees said, “It’s really inhumane to kick people out of their housing. I think it’s really upsetting how the school pretends they’re still supporting the arrestees, like they’re still in conversation with us. That’s total bullshit.”

They also elaborated, “The bad faith way that this is being approached by administrators, from all sides, in terms of implementation of suspension was unexpected.“

Njue also discussed how the decision to call the police on April 5 is hypocritical in light of Pomona College’s purported values of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

“Putting your students who are black through the [carceral] system is insane and incongruent with these ideals. You would think that having a black president or black administration would’ve prevented this from happening. But clearly there is no growth and no difference to a white [administration] like our previous white supremacist presidents who upheld apartheid and upheld the police state. Even our past presidents who were the literal people who were displacing indigenous people and stealing their cultural artifacts. There’s no difference between that and their new colorful cadre of administrators who propose themselves as representatives of those communities of color.”

Despite all of this, students are still committed to their original demands for divestment.

Another arrestee concluded, “What we did was a political move. We were arrested as a political move. So, yeah, I think we’ve refocused our efforts towards fighting for divestment.”

They said, “Divestment from Israel, it’s not about our conscience. It’s about life or death. It’s about what’s killing us. And the fact of the matter is that the attitudes and thought processes and the apparatuses of control that are currently genociding people in Palestine are connected to the same apparatuses that arrested us in that building. But we’re all focused on the fight for divestment and the fight for a liberated Palestine.”

Njue, Chapman and Truong echoed this statement as they ended their call with a resounding, “We’ll be back.”

Palestine

Palestine

Palestine

Undercurrents reports on labor, Palestine liberation, prison abolition and other community organizing at and around the Claremont Colleges.

Issue 1 / Spring 2023

Setting the Standard

How Pomona workers won a historic $25 minimum wage; a new union in Claremont; Tony Hoang on organizing

Read issue 1