October 2, 2023

I didn't read any books in high school. Everything was always incredibly boring and distant...

I didn’t read any books in high school. Everything was always incredibly boring and distant. I guess I just never liked the feeling of holding the words and steering my eyes across them. I always felt that I had very little idea of what I was supposed to be doing in my head. I wanted immediate, sensuous things. Everything else took too long, and I was so impatient.

Of course, books are all at least a little distant because the stuff in them is an appropriation. The writer is appropriating what they feel or think by squeezing it into words and the reader is appropriating the words by imagining access to a place akin to where the writer began. And the appropriation can get really close to a feeling or to describing something accurately and people can feel intensely understood, or inspired, or that they belong somewhere.

But I think I secretly felt that all my attempts at engaging with this appropriation were intertwined with an alienation that shadowed over everything in a scary and intense way. Like how talking about some things makes them lonely in a new way, like the appropriation and alienation touched all the way down. There’s a question that’s always bothered me and it’s taken on many forms. Like, is it better to know or to stay wondering? To speak or to die? And younger me, getting nervous about everything, deep down wanted to back out of all of it.

Of course I didn’t think about it in those words when I was younger. I mainly just noticed that no matter how many times I’d desperately ask someone, ‘Y’know what I mean?‘ the words would never work or feel right, even with therapists or with people who made it seem like they really knew what I meant. I don’t remember when I started to feel this way about things. Only a few scenes from before it began.

When I was around three, my mother would sing to me in Mandarin, a series of soft flowing tones and inflections. I knew not words but shapes of sounds and phrases. At school I spoke English, at home I exchanged simple, easy phrases in Mandarin with my mother. Something like, cover your legs you’ll get cold or, this morning I woke up with my neck sore. As I got older, maybe around seven, she insisted on speaking English in the house. For some reason, the content of our linguistic exchanges became too important to go misunderstood. So, perhaps for the sake of clarity, she used English when she needed to cuss at me.

She was not good at it. Mangled notes gripped themselves roughly, disjointed and twisted. Hearing her, I discovered a new sensation. Thick, almost violent, laboring through my veins, toward my chest. I wanted to apologize to her but English, and words, were all wrong. I think the moment that I, stripped of sound, watched my mother jam together amputated profanities in places they’ve never touched and was hit with the vague sort of feeling that I wanted to apologize from an impossible place, the place before our separation, was near the start of what I’m trying to get at.

As I progressed through my schooling, I grew decreasingly apologetic. I used my English against her fiercely. I was embarrassed at how clunkily she navigated public spaces and frustrated that she could not ease me through the problems that my peers’ parents helped them with. I acquired skills she lacked and gracefully navigated things that caused her deep anxiety. I grew to know, better than her, the fears she messily bore into me and what to do with them. It was a relief that reached shallower parts of my body.

At the moment we become aware that we need someone or something, separation has already opened up. Such an awareness stipulates the recognition that you and I are two things, not one. Here is where your body begins and here is where mine ends. And yet I need your body to persist as my own. But if you never left my side, I’d never need to know the difference between the two of us. We could be amorphous, organic, like running water. I would never need to embalm you, know your name.

Separation is the process of embalming things in order to use them because we need them. Embalming sensations into bodies, sounds into words. I don’t know if those are the right words for what I’m saying. I just mean that when we need something, there’s a separation, over and over again, and there’s something irreversibly alienating about it at every level. The ultimate embalming, that of desire, image, and all the movements inside the head and body, is theory.

Take psychoanalysis, for example. That odd relief when you discover that you are the way that you are because of that terrible thing that happened to you when you were eight, relief that things are precise, outlined and defined. Relief that you can capture gestures, that you can predictably trace and repeat the movements that have always been there. Relief that things are solid enough to pick up and hold and throw. Relief that something can swallow you whole like a soft membrane.

But now things are all forms, and we are outside of them because we know their shape and how they work. What happens to interiority? Shadowy and unpossessed, touching, all the time, everywhere. Now when I do something, or want something, and it has a name, it’s all different. People can speak its name, dismissing it. But the feeling, vague, all throughout the body, is just missed.

Sometimes people write, in many words, about how they can’t write about what they want to write and that ends up being what they wanted to write anyway. Or they contradict themselves so delicately that the inexpressible thing emerges in places that are private enough, like unexamined intuitions or fears folded into themselves many times. But it is not enough to call something unnameable and then look the other way. Or to name all the space around it, shaping the gestures. There’s no success in the thing I’m describing. What to do about it?

My education has been a process of embalming many things, a contrived dedication to the serious business of things that last a little longer. I owe to it my increasingly productive ability to understand and explain facets of my and others’ alienation, which is certainly materially significant. But in it lies a weary paradox. The more I try to carve out a life, the more of it I lose. It enters me differently, slips me by. Imagine how many things would become obsolete if there were no suffering. I wonder what a life is for. I wonder how things can be soft and slow again.

Maggie Li Zhang is from Cincinnati, Ohio. Her hobbies including being with Arlo and putting her hair in a ponytail.

Commentary

Palestine

Palestine

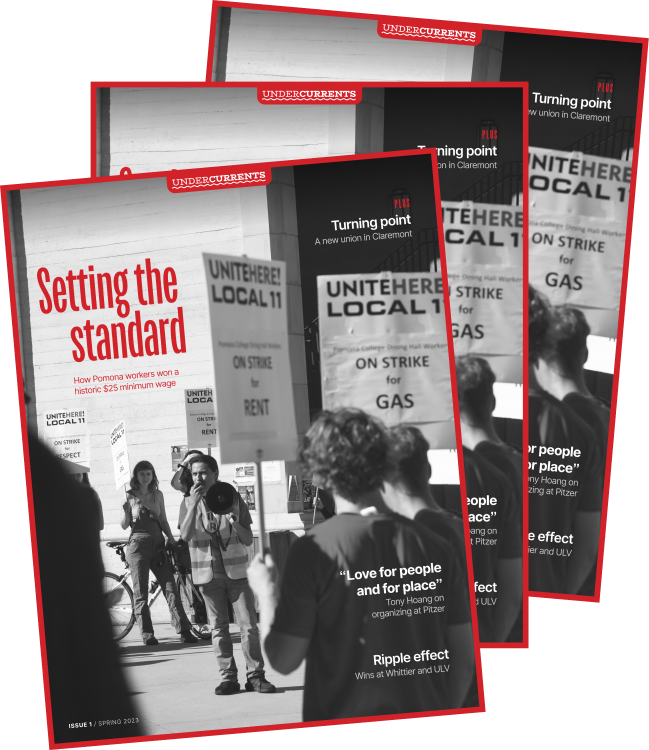

Undercurrents reports on labor, Palestine liberation, prison abolition and other community organizing at and around the Claremont Colleges.

Issue 1 / Spring 2023

Setting the Standard

How Pomona workers won a historic $25 minimum wage; a new union in Claremont; Tony Hoang on organizing

Read issue 1